I.4 |

Sources of Funding for Early Stage Ventures |

A. Introduction

Funding or capital is one of the critical components for the success of a business enterprise and the products it seeks to commercialize. There are various stages that a company goes through on its path to profitability. The initial stages are typically when it is the most vulnerable. This early stage is also when an entrepreneur/innovator finds it the most difficult to raise capital. Many times this also signals a transition from grant funding to venture thus requiring different skills, terms, approaches and sources of capital. This chapter describes the types and sources of funding that are available to an early stage company and important factors that must be considered when seeking early stage funding support. Financial investment is a highly regulated area and therefore it is important to fully understand the framework supporting capital financing. The resources range from informal gifts from family members to funding from the public markets. Finally this chapter offers a few important questions that the entrepreneur/innovator should carefully consider in preparation for raising funds for their venture.

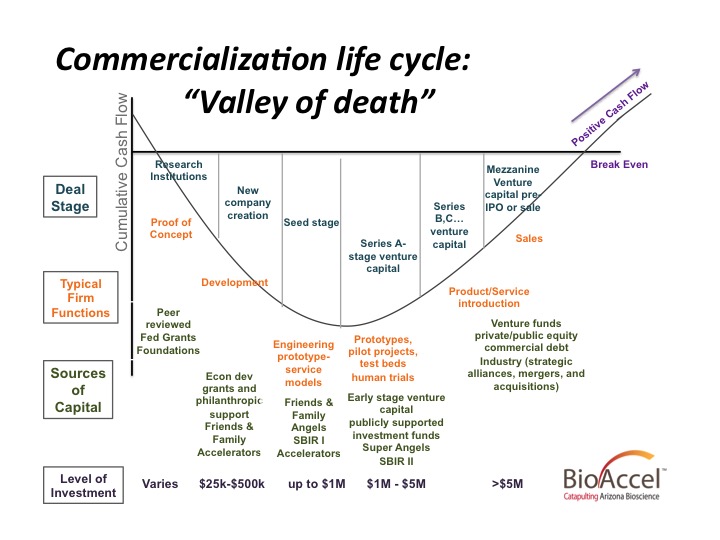

There are a variety of funding sources available to med-tech companies and they typically depend on the stage that the company is in. Fig. 1 shows the life cycle for the commercialization of a technology, the progression of a company as it tries to achieve positive cash flow and the sources of funds required to move through the commercialization life cycle.

Figure 1. Model of commercialization life cycle from start-up to market entry. Source: Battelle, BioAccel

B. Types of Funding

Before describing the various sources of funding for an early stage company it might be worth outlining the categories of funding that are available to a new company. The following are various types of funding that are available:

- Gifts- these are typically provided by close friends or family members and are given without contemplation of a return.

- Grants- these can come from local, state and federal sources. These funds are typically non-dilutive which means they are not provided in exchange for equity (an ownership interest) in the company. There is typically no repayment requirement for grants and they are given for a specific project or purpose. An example of one of these grants might be the Small Business Innovation Research Award (SBIR), which is offered by several agencies in the Federal government (1). Early stage, non-dilutive funding is important to a company and provides significant value to the founders.

- Equity investments- these are investments of cash given in exchange for an ownership interest in the company.

- Debt- these are loans to the company in which the company is obligated to repay under pre-determined terms. Typically the company and/or founders will need to meet a set of underwriting criteria. The loans can be either secured or unsecured.

- Convertible Debt- This is a debt instrument (or loan), which has the added feature of being convertible into equity. Convertible debts are sometimes referred to as bridge loans, convertible notes, convertible promissory notes and convertible bridge notes. A convertible note is a form of loan/debt that can be converted, automatically with set terms, or at the option of the note holder, into equity under predetermined circumstances (2).

- Factoring- If a company is fortunate enough to be receiving revenue from sales and happens to need help managing cash flow, the company can get short-term loans against its receivables (cash that is expected to come in from completed sales).

- Free cash flow- This is the most enviable position a company can find itself in and usually happens later in its life cycle. Once a company has received enough revenue that it is cash flow positive, it can use its free cash flow (cash after all the bills are paid) to fund expansion or other strategic projects.

C. Sources of Funding

Self (founders) family and friends

The first source of funding once an entrepreneur has decided to create a company is usually self, family and friends. At this very early stage in the company’s life there is little to no investable assets in the company other than the entrepreneur him/herself and their idea. Friends and family may provide small amounts of cash to the company primarily because of a personal interest and relationship with the entrepreneur. The business model while it is an important factor is typically not the main driver for family and friends investing at this stage.

It is important that the entrepreneur make the most out of these very limited funds. The entrepreneur needs to set very focused milestones, in writing, that will decrease both the technical and business risk of the company while beginning to demonstrate the value proposition of the business model. This increases the attractiveness of the company to the next stage of investors. The entrepreneur should manage expectations by advising these early investors of the high risk involved with their investment to preserve important personal relationships. If possible it is best to draw up formal agreements for the exchange of funds to ensure clear communication of the expectations and understandings.

Angel investors

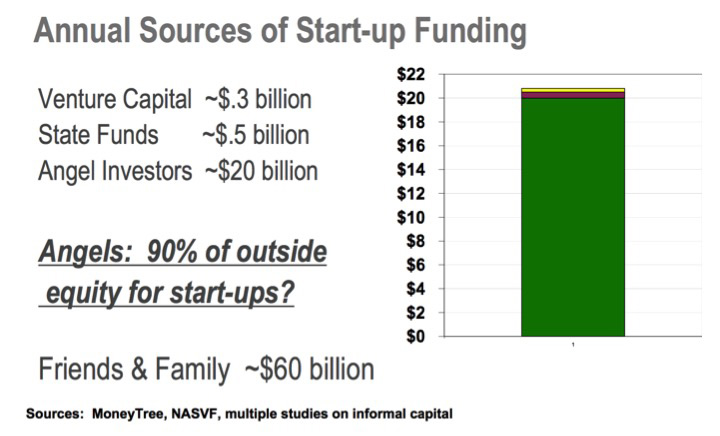

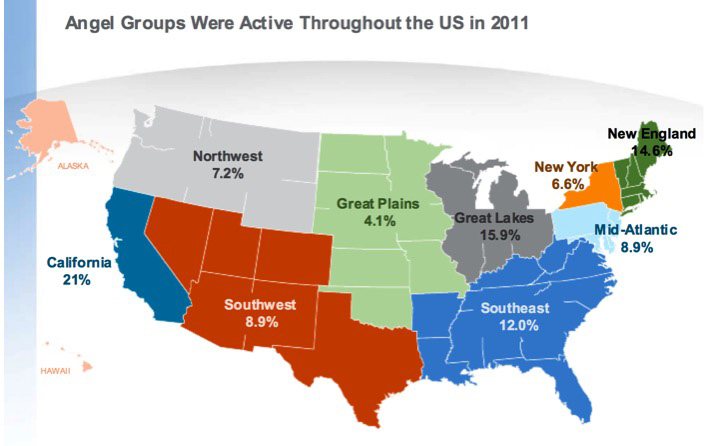

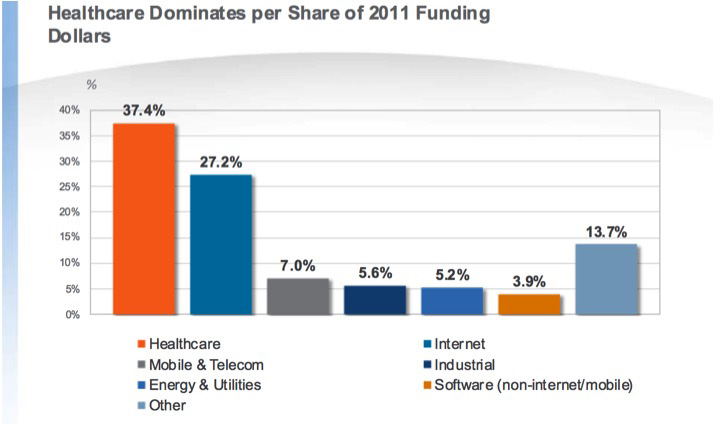

The next stage of investors is called Angel investors. An angel is typically a high net-worth individual who invests his or her own money in start-up companies in exchange for an equity share of the businesses. Angel groups have several organizations and associations that provide support for their efforts. One such association is the Angel capital Association (ACA) (3). The ACA is the North American trade association of angel groups and private investors that invest in high growth, early-stage ventures. According the ACA Angels account for 90% of equity investments in start up companies (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 shows that they are active all over the US (4). The predominate industry attracting Angel investing is healthcare (Fig. 4). The Angel Capital Association provides professional development for angel groups, family offices and private investors, delivers services and benefits to support the success of ACA member portfolio companies and serves as the promotional voice for the North American angel community and the public policy voice for the US professional angel community.

Figure 2. Annual sources and amounts of start-up funding for 2010. Green represents angel investors, red represents state funds and yellow represents venture capital.

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of angel group activity throughout the U.S in 2011. Source: HALO Report – 2011.

Figure 4. Distribution of investment capitol by industry sector in 2011. Source: HALO Report – 2011.

ACA recommends that entrepreneurs work with investors who are accredited investors (who meet requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission) and who can add value to the company via high quality mentoring and advice. Other important things to know about angels include:

- Many angels are former entrepreneurs themselves.

- They make investments in order to gain a return on their money, to participate in the entrepreneurial process and often to give back to their communities by catalyzing economic growth.

- Angels make a return on their investment when the entrepreneur successfully grows the business and exits it, generally through a sale or merger.

- It is estimated that angels invested 19 billion in more than 55,000 start-up businesses in 2008 (Source: Center for Venture Research).

- Angels tend to invest in companies that are located near them regionally (or to co-invest in a wider geography if a local investor they know and trust is involved).

For a variety of reasons, including reduced risk, Angels often function in groups. In an angel group, individual angels join with other angels to invest collectively in entrepreneurial firms. Angel organizations come in many forms, but all have certain characteristics including i) they meet regularly to review business proposals, ii) selected entrepreneurs make presentations to the membership of the group and iii) member angels decide whether to invest in the presenting business. Angels work together to conduct due diligence to validate the plans, statements and history of the entrepreneurial team.

Angel investors can be found in a number of ways. The best way is through local networking events. These events give the entrepreneur and Angel investors an opportunity to get to know one another and to better understand the specific interests of each other. Because some angels and angel groups are more likely to invest in firms that are recommended by people they know and trust, it is important to network in your community to gain a referral. Examples of people to contact include: entrepreneurs who are backed by angels or venture capitalists, attorneys who specialize in equity investment bankers, accountants and business counselors. Various Angel groups in a specific region can be located through Angel directories such as the ACA member Directory, or the Angel Resource Institute (5,6).

Because funding is so critically important to a company, it is tempting to chase cash wherever one can find it. This could be a major mistake. It is just as important to make sure that the potential investors are well matched with the business seeking funding. In addition to cash, investors should also bring valuable advice, mentoring and connections that can help ensure company success. A mismatch can spell disaster for the business. For example, if the business is a biotechnology company and the investors are only familiar with information technology (IT) companies, expectations can be completely out of alignment. A biotechnology company can have an exit horizon of over a decade versus an IT company that may exit in under three years. Milestones that are significant in a biotechnology company can be meaningless for an IT company and visa versa. This type of misalignment could lead to considerable disagreements about how the company should be managed. One must always remember that no matter how small the investment, the investor will always have an opinion and in many instances considerable control. The best outcomes are usually those when everyone, founders and investors, are on the same page in regard to the business and plans for growth.

Accelerators/incubators and state economics development programs

Before describing economic development programs it is best to describe business incubators and accelerators as a source of funding and other support for a med-tech business.

Incubators often house a large collection of different types of business – small and medium sized businesses of all stripes. The incubated companies are usually allowed to stay for an extended period of time (years), until they reach success, or until they fail. They usually “pay rent, although it is highly subsidized to be more affordable for the startup balance sheet. Businesses benefit from the financial arrangements and the camaraderie of working close to other new, growing businesses, which share the same struggles they do. Incubators often provide business and networking support that are helpful to growing companies. According to the national Business incubator association there are over 1200 business incubators in the U.S. (7).

Accelerators are one of the newest breeds of incubators. The most notable early innovators are YCombinator and TechStars (8).

Accelerators are different in that most have a time component to them – the clock on occupancy is ticking from the moment new companies enter the door and companies are expected to make enough progress to be out on their own in 3-6 months. Typically, there isn’t any rent to pay; simple shared office space is made available and most accelerators offer a stipend (~$15-25K is typical for 3-6 months) in exchange for equity in the startup (3-6% is common). Often the accelerator will offer rich interaction with people who can help startups grow – investors, lawyers, accountants, media and other entrepreneurs who have successfully grown businesses.

Accelerators typically have an application process and entrepreneurs are willing to move from their hometown to the location of the accelerator so they can get the experience that particular accelerator has to offer. And they have a final exam with investors, a “demo day”, in which they show off their progress and their ideas and see if they matriculate to an outside investment that will keep their company alive for the next period of growth.

For all these reasons, accelerators look more like a university experience – from the application, to the move, to the interactions with learned experts, to the time limit and finally, to graduation. Accelerators really stress the importance of quick traction and success, or consequently a “fail fast” mentality in the event of no or little business traction.

.The accelerator movement, having grown significantly in the last several years, is leading to the creation of industry-specific niche accelerators: a few examples are the Good Company Ventures for social entrepreneurs, FinTech Innovation Lab for financial services startups and Women 2.0 for female-founded startups (9).

There are other Medtech and Biotech accelerators that have come online in their industry sectors. Some of these programs offer seed level funding in the $100,000-$300,000 range (10,11).

At both the State and Federal government levels there is typically an economic development agency of some kind. The Federal economic development agency’s stated mission is to “lead the federal economic development agenda by promoting innovation and competitiveness, preparing American regions for growth and success in the worldwide economy” (12). These agencies provide grants and other forms of support to various incubators, accelerators and other programs. Funds from many of these grants can then be provided to early stage companies or used to secure matching funds from local sources that can be used to support these companies. Many of these programs do not allow funding to be used as seen capital.

Forty-two states now support programs that provide commercialization assistance to technology companies in an effort to more smoothly transition invention into innovation in the marketplace. The following are just a few examples, of state programs (13).

Arizona has both public and private efforts. For example, on the private side Arizona has BioAccel, a non-profit 501c314. BioAccel is dedicated to transforming discoveries into new business opportunities that accelerate commercialization of life science technologies. BioAccel focuses on diagnostics, therapeutics, devices, tools and services. The organization’s mission and staffing are dedicated to creating innovative programs that bridge the common resource gaps to efficiently enhance and develop technology into commercially available products and services. BioAccel will promote economic development in Arizona by providing: 1) Funding for proof of concept projects and seed capital for new company start-ups, 2) Technical and business expertise to assist entrepreneurs and early stage companies to move discoveries toward commercialization and 3) Educational opportunities to entrepreneurs, scientists, the public and students to better understand the requirements necessary to transform a life science discovery into a commercial success. Additionally BioAccel (14) has partnered with a local municipality, the City of Peoria, to create BioInspire, a device focused incubator that provides proof of concept, seed funding and facilities to qualified companies. Arizona has also formed the Arizona Commerce Authority. The Arizona Commerce Authority spearheads the state’s efforts to attract new business and expand businesses already excelling in the state. It’s led by a group of the most formidable, visionary private and public-sector minds in Arizona, coupled with the most talented staff implementing the strategy (15).

The State of Washington has earmarked a portion of its tobacco settlement dollars to fund bioscience R&D through the $350 million Life Sciences Discovery Fund (SB 5581) and in 2006 began allocating $35 million annually to research projects with economic development potential, including recruitment and facility enhancements. The state projects to leverage $1 billion in additional external research funding over its 10-year lifetime and create 20,000 jobs with about 15 years. The fund adopts a broad definition of the life sciences, encompassing biotech, pharmaceuticals, biomedical technologies, life system technologies, nutraceuticals, food processing, environmental and biomedical devices. It is governed by an 11-member board of trustees that evaluates grants for their potential health-care impact, future employment impact and geographic diversity. A 2-1 match from external sources is required.

CONNECT of San Diego, California, designed to link entrepreneurs with critical resources for success, provides networking opportunities as well as expertise to San Diego’s technology-based firms. Through the use of partnerships with the region’s industry-specific organizations and individuals, CONNECT since 1985 has assisted entrepreneurs and biosciences companies to commercialize ideas, patents and other opportunities surrounding university or private research institute R&D efforts. CONNECT’s initiatives include Springboard to assist aspiring entrepreneurs in transforming their business visions into reality. CEO CONNECT provides intimate peer group interaction to learn from and teach each other. CONNECT Entrepreneurs’ Roundtable, is a monthly program designed for capital providers, CEOs and presidents of San Diego-based early stage companies to nurture high technology start-ups.

The Texas Emerging Technology Fund was created by House Bill 1765 in an effort to speed up the process of commercialization within the state and create jobs and new companies in Texas from technology created in Texas institutions of higher education. The Fund is designed to boost eligible industries, which will lead to the creation of high-quality new jobs in Texas, and/or medical or scientific breakthroughs and includes biotechnology and the life sciences. One quarter of the Fund is dedicated to recruiting sought-after, top research talent to the state along with their team, patents and portfolio of potential emerging technologies. Another quarter of the Fund is to be used as matching grants to help draw down federal dollars and help push a technology through the commercialization phase.

The remaining one-half of the Fund is used by Regional Centers of Innovation and Commercialization (RCICs) to foster collaboration on emerging technologies between public and private entities and institutions of higher education. The legislation also contains provisions for failure to meet contract obligations or misuse of any grant money and the amount given to the Texas Emerging Technology Fund is up for review each biennium and is subject to legislators’ discretion.

The Pennsylvania Life Sciences Greenhouse Initiative was created through Act 77 of 2001 as part of a larger plan to ensure continued growth in Pennsylvania’s life sciences. The one-time investment of $100 million from the Tobacco Settlement into this initiative represents one of the largest technology-based economic development investments the state’s history. The program actively invests in early-stage life science companies and offers relocation and expansion incentives. The three regional organizations that comprise the initiative offer connections to angel investors, strategic partners and resources, along with business consulting services.

The Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholars Program was created by business and university leadership to attract the world’s pre-eminent scientists to Georgia’s universities to lead programs of research and development in areas with the most potential for generating new high-value companies, helping established companies grow and creating new high-wage jobs.

With the financial backing of the state legislature in 2010, the state’s research universities, private foundations and other supporters, the Eminent Scholars Program is marshaling the required talent and resources and driving an effective strategy for achieving these results.

To date, the Alliance has invested some $400 million, which has helped to attract more than 50 Eminent Scholars, leverage an additional $2 billion in federal and private funding, create more than 5,000 new technology jobs, generate some 120 new technology companies and allow established Georgia companies to expand into new markets.

To support the development of technology prior to company formation, the Alliance created VentureLab, a strategy for enhancing and accelerating the process of spinning new technology-based enterprises out of university research. The goals of VentureLab are to provide earlier and increased awareness by the business and investment community of university commercialization opportunities and to provide an easier and more efficient process for turning these technologies into new companies or new markets for established startups.

The Kentucky Innovation Act established the Department of Commercialization and Innovation (DCI) in 2000 within the Cabinet of Economic Development, which provides pre-seed funding to develop promising technologies.

Under the Kentucky Innovation Act, the General Assembly directed the Kentucky Science and Technology Corporation (KSTC) to invest in research and development activity to promote innovation and build a pipeline of new ideas and technologies that could add value to the scientific and economic growth in the Commonwealth.

South Carolina’s 2005 Innovation Centers Act led to the creation of SCLaunch! to aid Clemson University, the Medical University of South Carolina and the University of South Carolina in their commercialization efforts. SCLaunch! provides funding, mentoring and support services; an SBIR/STTR Phase I matching grant program; and a range of other smaller programs.

In 2004 and 2005 action by the General Assembly established the Venture Capital Investment Act to increase the availability of venture capital funds to help strengthen the state’s economic base and to support South Carolina’s economic development goals. The legislation created the Venture Capital Investment Authority to oversee the program that provides tax credits for private investment companies offering equity, near-equity or seed capital for companies in the state that are emerging, expanding, relocating or restructuring.

Venture capital funding

Venture capital has enabled the United States to support its entrepreneurial talent and appetite by turning ideas and basic science into products and services that are the envy of the world. Venture capital funds and builds companies from the simplest form – perhaps just the entrepreneur and an idea expressed as a business plan – to freestanding, mature organizations. According to a 2011 Global Insight study, venture-backed companies accounted for nearly 12 million jobs and $3.1 trillion in revenues in the United States in 2010.

Venture capital firms are professional, institutional managers of risk capital that enables and supports the most innovative and promising companies. This money funds new ideas that could not be financed with traditional bank financing, that threaten established products and services in a corporation and that typically require five to eight years to be launched.

Venture capital is quite unique as an institutional investor asset class. When an investment is made in a company, it is an equity investment in a company whose stock is essentially illiquid and worthless until a company matures five to eight years down the road. Follow-on investment provides additional funding as the company grows. These investment cycles called “rounds,” typically occurring every year or two, are also equity investment, with the shares allocated among the investors and management team based on an agreed financial “valuation.” But, unless a company is acquired or goes public, there is little actual value. Venture capital is a long-term investment. The range of investment made by a venture capital fund can range from small at $5 million to tens of millions. Various individual funds can also assemble together on a deal as a syndicate for even larger deals.

The U.S. venture industry provides the capital to create some of the most innovative and successful companies. But venture capital is more than money. Venture capital partners become actively engaged with a company, typically taking a board seat. With a startup, daily interaction with the management team is common. This limits the number of startups in which any single fund can invest. Few entrepreneurs approaching venture capital firms for money are aware that they essentially are asking for 1/6 of a person!

Yet that active engagement is critical to the success of the fledgling company. Many one- and two-person companies have received funding but no one- or two- person company has ever gone public! Along the way, talent must be recruited and the company scaled up. Any venture capitalist that has had an ultra- successful investment will tell you that the company broke through the gravity evolved from the original business plan concept with the careful input of an experienced hand (16).

Like the Angel investors, Venture Capitalists (VC) are usually members of an association or other organization such as the National Venture Capitalist Association (NVCA) (17). Also like the Angel groups the best way to get access a VC or VC fund is through networking events and introductions by trusted sources. Many accelerators/incubators, Chambers of Commerce and University Technology Transfer Offices host events for networking opportunities. The NVCA also holds various events that are posted on their websites.

Corporate/strategic investors

There are two ways that corporations can provide funds to start-ups: (1) through the purchase of equity in support of a research and development (R&D) or a licensing agreement, or (2) traditional venture investments. Corporate investments are often made by large companies (e.g. Johnson & Johnson) for strategic as well as financial reasons, since corporations seek to exploit synergies between projects in their internal portfolios and innovation occurring in the external environment. This type of funding can be less expensive to an innovator and can bring with it unique forms of leverage (e.g. access to established distribution channels, new technology, expertise). The association with a major corporation can also lend credibility to a young company. However, an innovator involved in this type of relationship may receive limited value in return for building the business. Conflicting agendas may rise as the corporate investor looks out for the corporation’s best interests (18). Inventorship of IP, shifts in corporate priorities and difficulty executing certain exit strategies can all be potential pitfalls in corporate investor partnerships. Nevertheless, by paying careful attention to alliance management and open, frank and frequent communication, these types of investments can prove very beneficial to the entrepreneur.

Small business administration/community banks

These institutions while they provide certain types of loans to small businesses, early stage or start-up companies are typically not good candidates for this type of funding. Usually the underwriting criteria (requirements to receive a loan) are such that it would be very difficult for a start-up company to qualify. For example, a revenue history is usually required. However, most start-up companies are pre-revenue. Many times the loan must be secured by assets of the company or personally if the company has yet to acquire a sufficient level of assets.

Investment banks/private equity firms/initial public offerings

These sources of funding are beyond the scope of an early stage company. They are listed here to complete the full continuum of funding sources for companies. For a more detailed discussion on this subject we encourage the reader to look at the chapter on Biodesign: The process of innovating medical devices (18).

Crowdfunding

With the proliferation of social media over the past decade, all kinds of interest groups have been given the opportunity to interact and execute change. From finding a great restaurant in the neighborhood to changing the power structure of a country, social media has proven to be a powerful force. The power of social media has not escaped the eyes of the start-up and investment community. For many years there has been a keen interest in having various groups invest in an area of research or a new start-up company for one reason or another. In exchange for their investment the investor would receive shares of stock in the company. While this sounds very straightforward there is a host of laws and regulations that both the investor and the company would need to comply with. Many of these laws date back to the 1930s. For example, under Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations only “accredited” (a person that meets various net worth requirements set by the SEC) investors would be allowed to invest. In addition the company would be subjected to a litany of registration, disclosure and reporting requirements. This is simply not practical for a new start-up. Fortunately as of the writing of this chapter the President has signed into law the “Jobs Act” (19). The provisions in this law seek to lower many of the requirements that have been impediments for early stage companies securing investment dollars. While there are still some modifications that will happen until 2013, essentially the framework is as follows:

Small private companies would be able to sell up to $50 million in shares as part of a public offering before having to register with the SEC and could have as many as 1,000 shareholders, up from the current cap of 500.

Entrepreneurs can raise equity capital from larger pools of small investors. This will enable startups and to use SEC-approved crowdfunding portals to raise money from anyone and everyone. The law stipulates that entrepreneurs can raise up to $1 million per year through those approved channels and seeks to limit potential financial damage to inexperienced investors by limiting the amount of money that an individual can invest, based on income.

Investors with incomes of less than $100K will be limited to 5 percent, or $2K, investments, while those who make over $100K/year will be limited at 10 percent, or $10K. Among other things, the law requires crowdfunding sites to provide further consumer protection, i.e. provide educational materials, which inform people of the risks inherent to the process.

Another notable measure: The legislation does away with the 500-shareholder rule, which put a cap on the amount of shareholders a company was allowed before having to register with the SEC. Under the JOBS Act, companies now have a longer grace period before being required to report financial data, are able to sell up to $50 million in shares and are now allowed as many as 1K shareholders before starting the process of going public (20).

There are various concerns that have been expressed about the new law and there will be challenges that will come up as the law is implemented. It will be important to for the entrepreneur to seek experienced counsel if he/she plans on exploring crowdfunding as a source of investment capital. Nevertheless, crowdfunding does represent yet another source of potential funding for early stage companies.

In almost all of the sections within this chapter, the entrepreneur/innovator will be required to make an argument as to why his/her early stage venture deserves funding. We are including at the end of this chapter a set of questions that the entrepreneur should consider and address before seeking funding. These are the types of questions that a potential funder/investor would want to get answers to. In an early stage venture it may not be possible to answer all of these questions, however, some thought should have gone into them.

D. Questions that Funders/Investors Like Answered

Technology or service concept

Questions funders like answered in this category include the following:

- Does the technology solve a REAL problem?

- Is the product/service concept clear? Does it make sense?

- Is path to commercial viability clear?

- Technical merit (does it work?)

- Are the advantages over the current technology/gold standard clear?

- Are the benefits sufficient or significant enough to drive adoption?

- Has the “killer experiment” been done or identified?

- Is there sufficient proof of principle or evidence of feasibility?

- Can product be manufactured at a reasonable expense?

- Is the technology scalable?

- Is there a viable reimbursement strategy (if applicable)?

- Is there a viable regulatory strategy?

Market size and dynamics

Questions funders like answered in this category include the following:

- How large is the market, realistically? What is the actual addressable population?

- What is the level of market demand/unmet need (perceived or real)?

- Does the company have realistic potential to obtain substantial (define?) revenues in the market?

- Is the decision making of purchasers and users well understood?

- Are the marketing and sales costs reasonable? Sales cycles? Distribution systems?

- Are the business relationships between referral sources, purchasers, providers and consumers well understood?

- What is the level of difficulty for adoption (Low, Med, High)?

- Does the company have a strong competitive position?

Management team

Questions funders like answered in this category include the following:

- Is the management team knowledgeable about the business?

- Can a great team be assembled to commercialize the product?

- Does the management team have a proven track record, particularly in this business?

Business model and financial requirements

Questions funders like answered in this category include the following:

- What are realistic revenue and expense projections for the company?

- How much capital will be required to reach positive cash flow?

- What are the realistic exit opportunities for investors in this deal?

E. Summary and Conclusions

Availability of funding for start-up companies is varied and at time complex. It is important to know and understanding the types of funding available and the best use of each type of funding at each stage of the commercialization life cycle. Access to funding is very competitive and it therefore founders should be well prepared prior to formally requesting and presenting their concepts to angels and venture capitalists. There are both non-profit and for profit groups available to help new business acquire the necessary technical and business expertise needed to advance technologies. Incubators and Accelerators are excellent resources to facilitate the advancement of technology and new companies in a way to reduce risk and maximize company value.

F. Selected Readings

- Biodesign: The process of Innovating Medical Technologies, by Zenios, Makower, and Yock, Published in 2010, Cambridge Univserity press ISBN 978-0-521-51742-3

- Angel Financing for Entrepreneurs: Early-Stage Funding for Long-Term Success, by Susan L. Preston. Published in 2007 by Jossey-Bass. ISBN number: 978-0-7879-8750-3

- Angel Investing: Matching Start-up Funds with Start-up Companies (Guide for Entrepreneurs, Individual Investors and Venture Capitalists), by Mark Van Osnabrugge and Robert Robinson. Published in 2000 by Josey-Bass. ISBN number: 0-7879-5202-8

- The Definitive Guide to Raising Money from Angels, by William H. Payne. Published in 2007 by Bill Payne and Associates. Available via www.billpayne.com.

- Every Business Needs and Angel: Getting the Money You Need to Make Your Business Grow, by John May and Cal Simmons . Published in 2001 by Crown Publishing Group. ISBN number: 0-609-60778-2

- Finding an Angel Investor in a Day, by The Planning Shop and Joseph R. Bell. Published in 2007 by The Planning Shop. ISBN number 0-9740801-8-7

- How to Raise Capital: Techniques and Strategies for Financing and Valuing Your Small Business by Jeffry A. Timmons, Stephen Spinelli and Andrew Zacharakis. Published in 2005 by McGraw-Hill. ISBN number: 0071412883

- How to Write a Great Business Plan, by William A. Sahlman. Published in 2008 by Harvard Business School Press. ISBN number: 978-1422121429

- New Business Ventures and the Entrepreneur, 6th ed., by Michael J. Robert, et. Al. Published in 2007 by McGraw-Hill. ISBN number: 978-0073404974

- New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century, by Jeffry A. Timmons and Stephen Spinelli. Published in 2008 by McGraw-Hill/Irwin. ISBN number: 978-0073381558

References

- http://sbir.gov/

- http://venturehype.com

- http://www.angelcapitalassociation.org/about-aca/

- http://www.angelresourceinstitute.org/halo-report/

- http://www.angelresourceinstitute.org/listing-of-groups/

- http://www.angelcapitalassociation.org/directory/

- http://www.nbia.org/

- http://ycombinator.com/

- Veek, A (2011) Accelerators vs. incubators. Pittsburgh Ventures. http://www.pittsburghventures.com/2011/01/accelerators-vs-incubators/ Accessed 12 April 2012

- http://www.BioAccel.org

- http://www.jumpstartinc.org/

- http://EDA.gov

- Pellerito, PM, Goodno, G (2012). Successful state initiatives that encourage bioscience industry growth. BioHealth Innovation. http://www.biohealthinnovation.org/index.php/bhi-news/112-successful-state-initiatives-that-encourage-bioscience-industry-growth-bio Accessed 12 April 2012

- http://www.BioAccel.org

- http://www.azcommerce.com/

- www.wisegeek.com/what-is-venture-capital.htm

- http://www.nvca.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=203&Itemid=637

- Zenioz S, Makower J, Yock P (2010) Biodesign: The process of innovating medical technologies. Cambridge, England.

- http://majorityleader.gov/uploadedfiles/JOBSACTOnePager.pdf

- Empson R (2012). Ready, set, crowdfund: president obama to sign jobs act tomorrow.