Basic Concepts in Device Development

Regulatory Assessment of Medical Devices in the European Union

Authors

Alan G. Fraser, MD

Robert A. Byrne, PhD

Tom Melvin, MD

Niall MacAleenan, MD

Olga Tkachenko, PhD

Paul Piscoi, MD

[Note: The information and views set out in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission.]

Introduction

The provision of health care in the European Union (EU) is a responsibility of each member state. The Treaty of Lisbon, however, confirmed that European member states shall cooperate to ensure a high level of human health protection; specifically, this includes “measures setting high standards of quality and safety for medicinal products and devices for medical use” (1).

The system for placing a medical device on the market in the EU is fundamentally different from the USA because there is no central agency equivalent to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Instead, evaluation of the evidence submitted by manufacturers is delegated to entities known as notified bodies. Notified bodies are companies that are designated and overseen by a national regulatory agency (known collectively as the “authorities responsible for notified bodies”). Designation empowers a notified body to assess if medical devices conform with all the requirements of the relevant legislation; this procedure is known as a “conformity assessment.” The certificate of conformity awarded by a notified body is valid across the EU regardless of where the notified body is located.

The EU system is in a state of transition because new laws were passed in 2017 that will govern the regulatory review of medical devices (2) and in vitro diagnostic medical devices (3); these change many important aspects of the European system. The law concerning medical devices will apply from May 2020, after a 3-year transition period, and that on in vitro diagnostic medical devices from May 2022.

In this section, we briefly review the history of legislation for medical devices in the EU and we explain how responsibilities are shared between different types of organizations. We refer to some aspects of the previous medical device Directives that are still in operation, but we concentrate on describing the new EU Regulations, particularly those aspects that concern higher-risk class IIb and high-risk class III medical devices. We aim to provide a step-by-step introduction to the European regulatory system that will be useful for innovators and manufacturers, particularly those who are based outside Europe.

It has been written in their individual capacity by clinical cardiologists involved in advocacy on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology (AGF and RAB), together with national regulators (TM and NMcA) and Scientific Policy Officers from the Health Technology Unit of the European Commission (OT and PP). The description has relevance to all medical devices.

Historical Overview

There are two main types of laws in the EU. Directives are instructions to member states that need to be integrated into their own law by national legislation, whereas Regulations, once they have been adopted by the European Parliament and by the Council of the European Union, apply directly in each country. Both Directives and Regulations constitute “secondary” legislation in the EU; the primary legislation is the Treaty on the European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Implementing acts, for which responsibility is delegated to the European Commission (EC), are correctly described as tertiary legislation.

When the first European legislation concerning medical devices was being considered in the early 1990s, it was decided to apply the so-called “New Approach” which had been developed by the European Economic Community (EEC; as the EU was then known) in the mid-1980s. That approach was designed for all manufacturing sectors and intended to ensure that there was a genuine single market, with all equivalent products being produced to similar standards and specifications whatever their country of origin. The legislation for the New Approach (4) established the system of notified bodies as organizations designated to verify the conformity and inspect the manufacturing processes of products on behalf of the relevant national regulatory agencies (competent authorities) for each sector within all member states. The system gave manufacturers access to the whole market after approval of their product by any notified body in any single country. A detailed guide prepared by the European Commission explains the origins of this system and the general principles of how it operates (5).

Directive 90/385/EEC (6) concerned active implantable medical devices and Directive 93/42/EEC (7) concerned (general) medical devices. Both were amended by a further Directive, 2007/47/EC (8), in 2007. The first detailed directive on in vitro diagnostic devices, 98/79/EC (9), was adopted in 1998. The provisions of those Directives remain in operation and will do so until the end of the transition periods for the new and strengthened EU laws on medical devices that were adopted in 2017. These are now Regulations: (EU) 2017/745 on Medical Devices (2) and (EU) 2017/746 on In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices (IVDs) (3).

When the EU developed a common system for the regulation of pharmaceutical products in 1995, it established a single central agency, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which now evaluates most applications for approval of new drugs in Europe. During the consultation leading into the new EU legislation for medical devices, the option of a European agency for medical devices was considered but not adopted. Differences between the regulatory environments in Europe and the United States have been described in detail elsewhere (10-12).

The European Commission is the central executive body of the EU. It oversees the regulatory system for medical devices, but it does not deliver it. Its Unit with responsibility for policy and for coordinating joint actions between national regulators is currently located in the Directorate General (DG) for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, called DG GROW. Another Unit, within the Health and Food Safety DG (DG SANTE), coordinates the joint assessments of notified bodies (13). The new system for obtaining independent expert advice about high-risk medical devices is being established with the support of the Joint Research Centre of the EC (DG JRC); that DG provides scientific and technical advice to other parts of the European Commission.

The EU regulatory system for medical devices is shared by all 28 member states, which have a combined population of 512 million (as of January 2018). National regulatory agencies have responsibilities to oversee the regulatory system for medical devices within their country, advise manufacturers, designate and supervise notified bodies, and monitor data provided by manufacturers. Reports from users during post-market clinical follow-up studies and from surveillance, including incidents, are collated by manufacturers and verified by notified bodies. The system is shared by Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway – members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) – which have a combined population of 6 million; their representatives can participate in the joint committees on medical devices in Brussels.

Through different types of agreement, Turkey and Switzerland have obtained the right to designate notified bodies that are recognized in the EU. The Swiss regulatory agency is a member of the committees in Brussels, and both countries accept CE-marked devices. In addition, the EU has mutual recognition agreements with other regulatory jurisdictions worldwide such as Australia and New Zealand. The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia can accept medical devices that have undergone formal evaluation and CE marking in Europe.

Principles of the EU System

According to the EU Regulations, a medical device is not actually “approved” in Europe; strictly speaking, it undergoes a “conformity assessment procedure” by a notified body, and then if it is judged to satisfy the relevant requirements, it is issued with a certificate of conformity. In turn that allows the manufacturer to place a CE mark on its product (for Conformité Européenne), and then to sell its device throughout the EU. The manufacturer has responsibility for the safety and performance of its device, while the legal responsibility for issuing the certificate of conformity rests with the notified body. The only exception concerns the lowest-risk devices (class I, with some exceptions) for which the manufacturer declares the conformity of its device without the need for verification by a notified body. For lower-risk classes a single certificate may cover many devices.

The main steps to be considered when seeking to place a new medical device on the European market are listed in Table 1. To help manufacturers to prepare to meet the requirements of the new Regulations, the European Commission has published several explanatory documents that are available from the EU website (Table 2). Guidance documents for manufacturers and notified bodies, concerning specific aspects of the medical device Directives, are also available; they are known as MEDDEV documents. Under the new Regulations they will be updated or replaced by new documents termed Medical Device Coordination Group guidance documents, in order to include specific references to any new requirements; some of these are expected to be published in 2019 or 2020. The Uniform Resource Locator (url) for the new guidance documents is included in Table 2. A report on the progress in the rolling implementation plan for the new Medical Device Regulation 2017/745 (MDR) is also available.

Table 1. Major Steps for Conformity Assessment of a Medical Device in the EU

| 1 | Have or establish a legal entity in at least one EU member state; otherwise, a non-EU manufacturer needs to appoint an Authorised Representative to act on its behalf. |

| 2 | Develop plans for clinical evaluation of the new device, including – in consultation with the national regulatory authority for medical devices in one of the EU member states – plans for clinical investigations if required for that risk class. An outline of any prospective clinical investigation (or trial) should be registered in the Eudamed database. |

| 3 | If desired (this step is optional), consult also with the Expert Panel in the relevant specialty, for independent advice about the design of the proposed clinical strategy. |

| 4 | Undertake the preclinical testing and clinical evaluation, including any clinical trial(s), as approved by the regulatory authority. |

| 5 | Prepare and submit a technical file for the device, including all the results from preclinical studies and clinical studies, to a notified body (NB) of your choice that is designated to evaluate that type of device. The submitted data includes a Clinical Evaluation Report (CER). |

| 6 | The application should also include the manufacturer’s plan for post-market clinical follow-up, and the draft Summary of Safety and Clinical Performance (SSCP) that after validation will be uploaded to the EU Eudamed portal. |

| 7 | If certification for the device is being sought on the basis of equivalence to a device that has already been certified and that is already on the market, then the manufacturer of the new device must have a contract with the manufacturer of the equivalent device allowing full access to the relevant data of that device. |

| 8 | The NB reviews all the data submitted by the manufacturer, and it prepares a Clinical Evaluation Assessment Report (CEAR). |

| 9 | For class III implantable and class IIb active devices administering or removing medicines, if the high-risk device is new, if it may have possible major clinical impact, or if it belongs to a category of devices for which there has been either a significant adverse change in the benefit-risk profile or a significantly increased rate of serious incidents, then the clinical evidence from the manufacturer and the CEAR written by the NB will be reviewed by an independent expert panel appointed by the EC. |

| 10 | The expert panel will decide within 21 days whether or not it intends to provide an opinion. If it does, the NB will receive the opinion within 60 days from the date of receipt of the files by the Commission. This opinion will be made publicly available. |

| 11 | The NB is free to decide if it accepts the advice from the expert panel, but if it does not, then it must justify its decision in a statement that will be publicly available. |

| 12 | If the NB determines that the device meets the relevant requirements, with an acceptable balance of benefit against risks, then it issues a certificate of conformity to the manufacturer. |

Table 2. Sources of Information from the European Commission

| Site | URL | |

| European Commission website concerning medical devices | https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices | |

| Updated progress report on the implementation of the new Regulations | https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices/new-regulations_en | |

| Legally non-binding guidance documents, concerning the EU Regulation 745/2017 | https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices/new-regulations/guidance_en | |

| Explanatory documents for current EU legislation (Medical Device Directives) | https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices/current-directives/guidance_en | |

| Factsheets for Manufacturers of Medical Devices | ||

| Step by step Implementation model: medical devices | https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/30905 | |

| Exhaustive list: requirements for medical device manufacturers | https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/30961 | |

| Factsheet for manufacturers of in-vitro diagnostics medical devices | https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/31202 | |

| Step by step Implementation model for in-vitro diagnostic medical devices | https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/30907 | |

| Factsheet for Authorized Representatives, Importers and Distributors of Medical Devices and in vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices | https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/33862 | |

Legal Requirements for Manufacturers Aiming to Place a Device on the EU Market

Before a manufacturer can place its device on the market in Europe (but not before it can approach a notified body), it must have a legal presence in the EU. It can be legally incorporated, or it should have a subsidiary that is registered in any EU member state. Otherwise, it needs to appoint a European company that will represent its interests; these economic operators are known officially as “authorized representatives” and they have specific responsibilities and liabilities that are described in the Regulations (Article 11) (2). For example, if the manufacturer fails to meet its legal obligations, then the authorized representative becomes legally accountable. Contact details for some authorized representatives are available from the website of their trade association, the European Association of Authorised Representatives (at http://www.eaarmed.org).

Any company that sells medical devices must employ designated staff who are responsible for its compliance with the EU medical device Regulations, for example to manage risks and to ensure that there is an effective quality control system. Micro- and small enterprises are allowed to have such a person at their disposal rather than to employ one directly. The qualifications and experience of the person responsible for regulatory compliance are now strictly defined (Article 15) (2). The duties of the manufacturer include maintaining technical documentation, reporting incidents and field safety corrective actions, and having liability cover for damage compensation (Article 10) (2).

Determining the Risk Class of a Medical Device

A manufacturer can determine the risk class of its medical device by applying the classification rules that are described in Annex VIII of each EU medical device Regulation and summarized for general medical devices in Table 3. The manufacturer’s determination is reviewed by the notified body. Further advice is provided in EU guidance documents (14), which are being updated for the new Regulations. Guidance for classification of IVDs is also in preparation. If there is doubt in a particular case, then it may be helpful to consult a summary of views agreed by EU competent authorities in certain borderline cases (15). National authorities can also decide the appropriate classification of a device, if there is a conflict of views between the manufacturer and the notified body.

Table 3. Summary of EU Classification Rules for General Medical Devices (2)

| Risk Class | Types of Devices* ¶ | Examples |

| Class I | Noninvasive devices | Urine collection bottles, hospital beds, stethoscopes, eye-occlusion plasters, dressings for superficial wounds |

| Invasive devices for transient use | Enema devices, examination gloves | |

| Class IIa | Noninvasive devices intended for channeling or storing blood, body liquids, cells or tissues, liquids or gases for infusion, administration or introduction into the body | Tubing/syringes intended for use with an infusion pump; fridges specifically intended for storing blood or tissues

|

| Non-invasive devices which come into contact with injured skin or mucous membrane (except for barrier function) | Polymer-film or hydrogel dressings

|

|

| Invasive devices for short-term use | Tracheal tubes, indwelling urinary catheters, contact lenses | |

| Surgically invasive devices intended for transient or short-term use | Surgical clamps, drainage tubes, skin closure devices

|

|

| Active therapeutic devices intended to administer or exchange energy | Muscle stimulators, TENS devices, cryosurgical equipment, hearing aids

|

|

| Active devices intended to administer and/or remove medicinal products | Suction equipment, feeding pumps

|

|

| Software intended to provide information which is used to take decisions with diagnosis or therapeutic purposes | Standalone prognostic software used to guide preventive treatment | |

| Devices specifically intended for recording of diagnostic images generated by X-ray | X-ray films | |

| Class IIb | Surgically invasive devices intended for transient or short-term use with a biological effect or that are absorbed | Absorbable sutures

|

| Implantable devices and long-term surgically invasive devices | Shunts, stents, nails and plates, peripheral vascular stents and grafts | |

| Active therapeutic devices intended to administer or exchange energy (potentially hazardous) | External pacemakers, lithotripters, incubators for babies, ECT equipment

|

|

| Active devices intended to emit ionizing radiation and intended for diagnostic or therapeutic radiology | Therapeutic or diagnostic x-ray sources

|

|

| Devices used for contraception or prevention of the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases (unless implantable) | Condoms | |

| Class III | Surgically invasive devices intended for use in heart or central circulatory system or CNS | Temporary pacing wires, cardiac ablation or neurological catheters |

| Implantable devices and long-term surgically invasive devices intended for use in heart or central circulatory system, or CNS | Prosthetic heart valves, spinal stents, cardiovascular sutures, IABP | |

| Implantable devices and long-term surgically invasive devices intended to administer medicines or that are breast implants or surgical meshes or total or partial joint replacements | Drug-eluting stents, contraceptive IUDs, antibiotic bone cement, breast implants, vaginal meshes, hip replacements | |

| Software intended to provide information which is used to take decisions with diagnosis or therapeutic purposes if such decisions may cause death or irreversible deterioration of health | Standalone software that is used to determine if patients with severe disease should be given treatment | |

| Devices manufactured utilising tissues or cells of human or animal origin | Biological heart valves, implants/dressings made from collagen | |

| Devices incorporating or consisting of nanomaterial with a high or medium potential for internal exposure | Synthetic bone graft

|

|

| Active therapeutic devices with an integrated or incorporated diagnostic function which significantly determines the patient management by the device | Automated external defibrillators, closed loop systems |

Note that these are indicative examples only. The actual determination of the risk class of any particular device is part of its certification process.

Provision for the classification of medical devices is made in MDR 2017/745 Chapter V Section 1 Article 51: Devices shall be divided into classes I, IIa, IIb and III, taking into account the intended purpose of the devices and their inherent risks. Classification shall be carried out in accordance with Annex VIII. Annex VIII sets out details of 22 classification rules intended to enable classification of any medical device into one of the four categories. Guidance documents for the classification of medical devices under MDR 2017/745 are not yet available. MEDDEV 2.4/1 Rev. 9 (June 2010) provides useful guidance and examples for rules relating to MDD 93/42/EEC, many of which apply to MDR 2017/745; ¶ definitions provided are simplified from the original source document which should be referred to for more detailed information; * unless another rule applies.

Active therapeutic device means any active device used to support, modify, replace or restore biological functions or structures; Active device intended for diagnosis and monitoring means any active device used to supply information for detecting, diagnosing, monitoring or treating physiological conditions, states of health, illnesses or congenital deformities; transient = continuous use < 60 minutes; short-term = continuous use < 30 days; long-term = continuous use > 30 days.

Software can be a medical device. When software is an integral part of a medical device, then it is judged within the same class. If faulty or erroneous operation of the software may have serious clinical consequences, then the applicable risk class may be higher. Stand-alone software with a medical function is classified in its own right, and separate guidance is available (16).

Selecting a Notified Body

All notified bodies that have been designated to assess medical devices are listed in the “New Approach Notified and Designated Organisations” Information System, otherwise known as the Nando database, under the relevant EU legislation (http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/nando/). Any manufacturer is free to select any notified body to assess its medical device, as long as it has been designated for that type of device.

The competent authority with which a manufacturer may need to deal in relation to its notified body is the authority of the country in which the manufacturer or its authorized representative operates.

Clinical Evaluation of Medical Devices in the EU

Requirements for Clinical Evaluation

Each manufacturer of a medical device is responsible for conducting a clinical evaluation of its device, which is defined by Regulation (EU) 2017/745 as a systematic and planned process to continuously generate, collect, analyze and assess the clinical data pertaining to a device in order to verify the safety and performance, including clinical benefits, of the device (Article 2.44). Clinical evidence is defined as both clinical data and the assessment of that data, including the results of studies, which together are of a sufficient amount and quality to allow a qualified assessment of whether the device is safe and if it achieves the intended clinical benefit(s) (Article 2.51). Clinical benefit is defined as the positive impact of a medical device on the health of an individual, expressed in terms of “meaningful, measurable, patient-relevant clinical outcome(s)” (Article 2.53).

For most types of devices, the manufacturer has to submit the outcome of its clinical evaluation for review by the notified body, as part of the technical documentation. The Regulation places the onus on the manufacturer to justify the level of evidence that is required, depending on the characteristics and intended purpose of the device (see Article 61). The manufacturer will need to justify the acceptability of the benefit-risk ratio of the device and present sufficient clinical evidence. Specific obligations for certain classes of devices are summarized in Table 4, which also gives references to the relevant MDR articles. One outcome of the European regulatory reforms has been to raise the standards of clinical evidence required for new high-risk medical devices – meaning all permanent implants as well as class III devices – before they will gain market access.

Table 4. Some Specific Requirements Regarding Clinical Data Concerning Medical Devices in Europe

| Requirement | Applicable Classes of Device | Legal Reference* |

| Clinical investigation | Class III and implantable devices | Article 61 |

| Clinical evaluation consultation procedure | Class III implantable, and class IIb active devices that administer or remove medicinal products | Article 54 |

| Summary of safety and clinical performance | Class III and implantable devices | Article 32 |

| Production of periodic safety update report (PSUR) | Class II and III | Article 86(1) |

| Submission of PSUR to notified body | Class III and implantable | Article 86(2) |

*Refers to Articles in Regulation (EU) 745/2017 (2).

The new EU Medical Device Regulations define clinical data as information concerning safety and performance that is generated from the use of a device and that can be sourced from clinical investigations of the device or of an equivalent device, as well as from reports published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, and from information derived from post-market surveillance. There are also specific technical, biological, and clinical criteria that define when a device can be established as equivalent to another device that has already received a certificate after a conformity assessment procedure. As a result of these factors, even for a low-risk device a generic literature review without a demonstration of equivalence, if relevant, and without meeting the definition of clinical data and generating sufficient clinical evidence would not be sufficient.

For all class III and implantable medical devices, clinical investigations are obligatory – apart from some limited exemptions that are specified in MDR Article 61, clauses 4-6. EU guidance document MEDDEV 2.7.1/revision 4 provides an overview of requirements for clinical evidence and gives examples of what types of clinical evidence are acceptable (17). It was prepared in the context of the Directive and will be updated to bring it in line with the MDR. It indicates what evidence can be presented when a manufacturer wishes to obtain a new certificate for an iterative change to a device that has already been approved. It describes what evidence should be submitted when a manufacturer proposes that its device should be approved on the basis of equivalence to an existing device. For implantable devices and class III devices, Regulation (EU) 2017/745 lists conditions that must be fulfilled in those circumstances. If a manufacturer wants to claim that its new device is equivalent to a device made by another manufacturer that has already been approved, then there must be a formal contract between the companies that grants the applicant full access to the data from the company that makes the device to which it claims equivalence (2).

Applications for approval of the design of a clinical investigation should be made by its sponsor to one of the national competent authorities (see Articles 70 and 78). In future, if an investigation is to be performed in several European countries, there will be the option of a coordinated assessment by several competent authorities (see Article 78 of the new Regulation) (2). The sponsor also has to notify the competent authorities in the countries where the study was performed, at the end of the clinical investigation, and provide a clinical investigation report (Article 77). The clinical data obtained from the clinical investigation will then be one part of the clinical evaluation of the device that is submitted to the notified body. Under the MDR, clinical investigations including trials must be recorded and reported in the European Union Database on Medical Devices (Eudamed) database (see below, section 6.3), parts of which will be publicly accessible.

For devices other than class III and implantable devices, clinical investigations are not mandatory, but every device must be supported by a clinical evaluation. The Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) submitted by the manufacturer still has to satisfy all of the requirements currently listed in Annex X of the Medical Device Directives, and so it has to include more than a summary of benefits relative to risks. With respect to the new MDR, the manufacturer has the opportunity to justify if it considers that demonstration of conformity based on clinical data is not appropriate (see Article 61.10) and that only nonclinical testing is required; in that case the CER can consist of a review and critical evaluation of the literature and any clinical investigations already available, as well as consideration of currently available treatment options for that purpose. Article 61.6.b lists a range of devices such as sutures and staples for which a derogation from the requirement to conduct clinical investigations may be available.

The Clinical Evaluation Consultation Procedure (CECP)

Under the MDR, there will be a new procedure for the independent review of the notified body’s assessment of the manufacturer’s clinical evaluation, for Class IIb active medical devices that are intended to administer and/or remove a medicinal product, and for all class III implantable medical devices. This is called the Clinical Evaluation Consultation Procedure (Article 54). The particular criteria that will be applied to select which device applications should undergo this new review process are whether the device is new and may have possible major clinical impact, if there has been a significant adverse change in the benefit-risk profile for its type, or if there has been a significantly increased rate of serious incidents for its type (MDR Annex IX, paragraph 5.1.c).

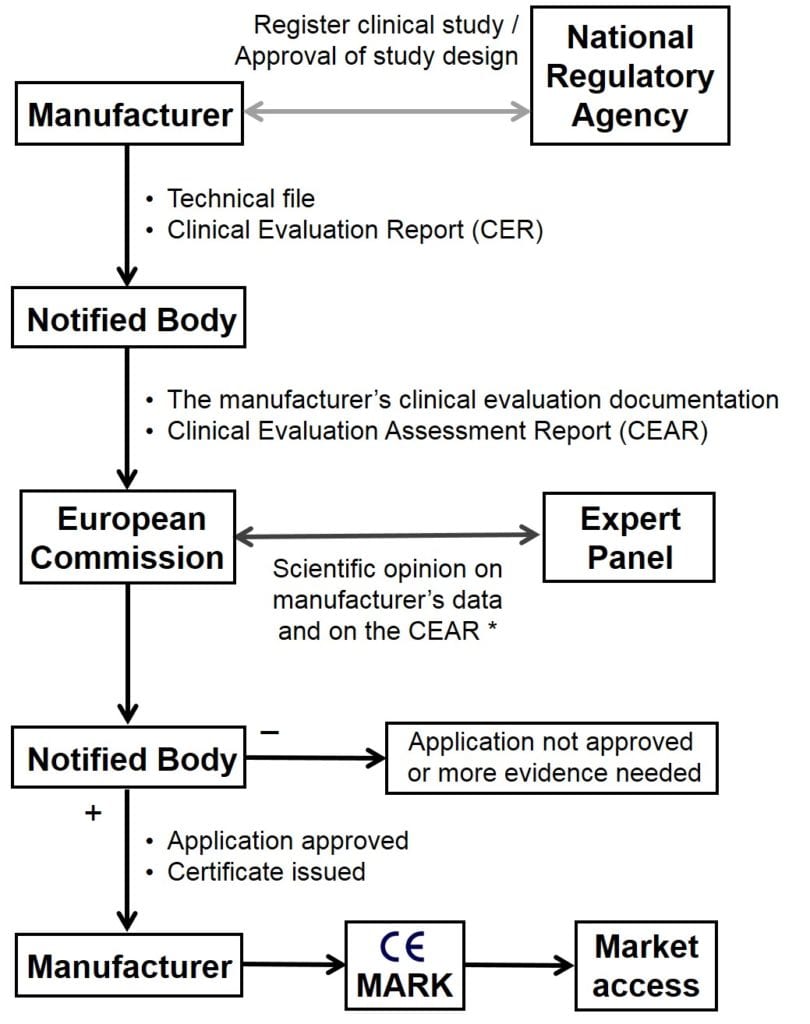

Under this procedure, after completing a review the notified body will forward all clinical evidence submitted by the manufacturer including the manufacturer’s Clinical Evaluation Report (CER), together with the Clinical Evaluation Assessment Report (CEAR) that the notified body itself has written, to the European Commission (Figure 1). In turn the Commission will forward these to an expert panel consisting of scientists, engineers and clinical specialists with particular knowledge of the relevant medical specialty or type of device. The panel must decide within 21 days if it intends to give an opinion, and if it does then it must submit its opinion to the European Commission within 60 days of receipt of the documents.

Other responsibilities of the expert panels will include providing advice to manufacturers concerning their “clinical strategy” for investigations of their device, and advice to the European Commission and member states about any concerns related to safety and performance of devices. Thirdly, they will contribute to the development of guidance and common specifications (see Article 106) (2).

Figure 1. Overview of the EU Conformity Assessment Procedure

*Note that a scientific opinion from an expert panel (CECP) is provided only for certain class IIb and class III devices, as discussed.

Applicable Medical Device Standards and Guidance

As already mentioned, EU guidance documents concerning medical devices are accessible via the European Commission website (europa.eu; see Table 2).

There are obligatory European common specifications for some in vitro diagnostic medical devices (18), but the EU has only published one guidance document concerning a specific type of non-IVD medical device. That relates to coronary stents (19). This document is being revised to take account of current knowledge, as summarized in two detailed advisory reports written by an expert task force of the European Society of Cardiology (20,21). The revised document will be the basis for the first common specification – a tertiary legal act laying down the minimum specifications to be fulfilled for a specific type of device to comply with certain requirements of the new MDR. Requirements for other common specifications will be identified by regulators, if there is a need to address public health concerns for any specific devices (see Article 9).

Standards for many types of medical devices are produced by international standards bodies including the International Standardization Organization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). Their standards can be adopted by their European equivalent organizations (European Committee for Standardization [CEN] and European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization [CENELEC]). European standards, compliance with which can provide full or partial presumption of conformity with EU legal requirements, can be published by the EC as harmonized standards. They are listed in the Official Journal of the European Union; about 300 standards are cited in the most recent list (22).

Most technical files submitted by manufacturers to notified bodies will refer to European standards that reflect ISO standards relating to medical devices, for example those on clinical investigation and good clinical practice (EN ISO 14155:2011, currently completing a major revision) (23) and on quality management (24).

An example relates to the fast-developing field of devices for replacement or repair of heart valves. There are no specific EU guidance documents, so the standards that are applied are those developed by Working Group 1 of Sub-Committee 2 of Technical Committee 150 of the ISO (ISO/TC 150/SC 2/WG 1), concerning “Cardiovascular implants and extracorporeal systems.” There are three standards on prosthetic heart valves, all of which are currently undergoing revision (ISO 5840 parts 1, 2, and 3) (25-27) and there is a new standard concerning devices for valve repair (ISO 5910) (28). The related harmonized European Standards are published by CEN Technical Committee 285 (29-31). An important by-product of the revision of the standards has been the independent publication of academic papers that define objective performance criteria for surgically implanted heart valves (32) and that calculate the sample sizes that would be needed for sufficient statistical power to demonstrate that a new transcatheter heart valve meets an acceptable safety standard (33). For surgically implanted heart valves, the minimum cumulative experience that should be reported for a new heart valve designed for a single position is 800 patient-years (26).

Post-market Clinical Follow-up and Surveillance

In Europe as in other regulatory jurisdictions the manufacturer is responsible for post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) of its device (34). This is a continuous process that updates the clinical evaluation (Article 83, and Annex III). Data gathered shall be used to update benefit-risk determination, to improve risk management, and to identify any need for a preventive or field safety corrective action.

Notified bodies are responsible for re-certification of medical devices, and for continuous surveillance of PMCF reports from the manufacturer. Competent authorities are responsible for monitoring other reports and vigilance data.

Assessment of the Manufacturer’s Plans by the Notified Body

The manufacturer must include separate plans for PMCF and for post-market surveillance of its device in the documentation that it submits to the notified body. These will address how the manufacturer will collect information concerning serious incidents, collate data on any undesirable side-effects, analyze information from trend reporting, and monitor information that is available from any relevant specialist databases (including registries run independently by academic institutions or medical associations) and information that is provided by users.

Periodic Safety Update Reports

Manufacturers of class I devices need to generate a post-market surveillance report and be able to provide it to the competent authorities upon request. Every manufacturer of a class II or class III device is required to produce a Periodic Safety Update Report (PSUR) about its device. For class IIb and class III devices the PSUR needs to be submitted for review to the notified body, at least annually; for class IIa devices the requirement is at least every 2 years. The PSUR should be used to update the Summary of Safety and Clinical Performance (SSCP; discussed below) that is made available for health care professionals and patients.

Monitoring by National Competent Authority

Manufacturers have obligations to report serious incidents and field safety corrective actions. National competent authorities monitor and evaluate this information. Reports of serious incidents and serious adverse events during clinical investigations will be uploaded to the Eudamed database and shared with regulatory authorities in all EU member states.

Non-serious incidents, and expected undesirable side-effects, must also be recorded, and manufacturers must report statistically significant trends in their frequency and/or severity.

The European Commission has been designated responsibility, in collaboration with the member states, to establish systems and processes to actively monitor the data uploaded to the Eudamed database, in order to identify trends, patterns or signals in the data that may reveal new risks or safety concerns (Article 90).

Transparency of Implant Data and Clinical Evidence

The EU has had legislation concerning freedom of information since 2001 that requires all documents of the European Commission and of all its agencies to be made directly accessible to the public to the greatest possible extent (35). This legislation applies to the European Medicines Agency, which therefore has a policy of full transparency (extending to clinical databases, results of preclinical tests and clinical studies, and regulatory decisions), but it does not apply to notified bodies since they are independent commercial organizations (36). Nonetheless, Regulation (EU) 2017/745 states that “transparency and adequate access to information .. are essential .. to empower patients and health care professionals and to enable them to make informed decisions” (Recital 43).

Unique Device Identification

From 2020 the European Union will fully implement the system for Unique Device Identification (UDI) of medical devices that has been developed in conjunction with the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) and pioneered by the FDA in the USA. This will mean that individual patients with particular devices can be tracked, in the case of any device alerts or recalls.

Patients who receive a device implant will in future be provided by the hospital with an implant card that will include their UDI (some dental implants will be exempted from this rule). The manufacturer will submit a draft of its implant card, and details of its UDI, as part of its technical file to the notified body.

Summary of Safety and Clinical Performance

The manufacturer of each class IIb implantable device and each class III medical device is now required to summarize the main safety and performance aspects of its device and the outcome of its clinical evaluation. This information will be published in a document called the Summary of Safety and Clinical Performance that will be publicly available via the Eudamed portal (MDR Article 32).

Detailed guidance on the contents of each SSCP will be published by the European Commission in 2019. As stated in Article 32, these will include the intended purpose of the device with its target populations; specific indications and any contraindications to its use; any residual risks and undesirable effects, warnings or precautions; a summary of the clinical data from conducted investigations of the device and an overall summary of its clinical performance and safety; ongoing and planned post-market clinical follow-up studies; possible diagnostic or therapeutic alternatives; clinical data obtained from the post-market surveillance plan; and an analysis of clinical data from medical device registries. There will be a shorter section for patients, written in appropriate language. The SSCP will be available in the native language for each country where the device will be sold. The manufacturer will need to submit its SSCP with the other documentation to the notified body for validation.

The Eudamed Portal

As part of the provisions required by the new medical device Regulations, there will be a major expansion in the functions and use of the EU portal for medical devices, called Eudamed. This will be maintained by the European Commission and it will include documents submitted by manufacturers, notified bodies, and national competent authorities (regulatory agencies). Health care professionals and the public will have access to much of the content within Eudamed.

All devices with their UDI and with the certificates issued by notified bodies will be registered. Once the Eudamed database has become established, there will be an accessible list of all medical devices that have been placed on the European market. Another very important function of the Eudamed portal is that it will provide a central register for all clinical investigations of medical devices that are performed in the EU. All studies must be registered by manufacturers, and once available their results will be uploaded to the database. The main findings from clinical investigations of high-risk devices will be summarized in the SSCP.

In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices

There has also been a major revision of the Regulation concerning the conformity assessment of in vitro diagnostic medical devices in Europe (3). The new requirements will substantially increase the proportion of in vitro diagnostic devices that will undergo formal evaluation by a notified body.

Risk Class

Annex VIII in Regulation (EU) 2017/746 gives classification rules for in vitro devices. The highest risk, class D, are those whose function is to detect the presence of, or exposure to, a transmissible agent in blood or human tissue, in the context of transfusion, cell therapy, or transplantation, as well as any transmissible agent that causes life-threatening disease with a high or suspected high risk of propagation; and those which determine the infectious load of a life-threatening disease where monitoring is critical for managing the patient. Certain blood grouping and tissue typing devices are also placed in class D. Devices for obtaining genomic and proteomic profiles are placed in class C.

Sufficient Clinical Evidence

Article 56 of Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on IVDs states that confirmation of conformity with the relevant general safety and performance requirements “shall be based on scientific validity, analytical and clinical performance data providing sufficient clinical evidence.” The Regulation includes detailed requirements for reporting the performance characteristics of a diagnostic device (test). Annex XIII (Part A, at paragraph 1.2.3) states that demonstration of the clinical performance of an in vitro diagnostic device will be based on one of, or a combination of, the following: clinical performance studies, the scientific peer-reviewed literature, and published experience gained by routine diagnostic testing.

Reference Laboratories

There is provision in Regulation (EU) 2017/746 for the designation of specialist EU reference laboratories. In particular, these laboratories shall perform batch testing of class D devices and verify their performance and compliance with any common specifications. They may also have other functions such as contributing to the development of new common specifications.

Health Technology Assessment

Although there is a shared European system for the conformity assessment of medical devices, subsequent assessments about the added value of a device compared to new or existing health technologies – as the basis for decisions about provision and reimbursement – are currently done separately within each EU member state. Manufacturers thus need to apply individually for evaluation of their CE-marked device by an agency responsible for HTA in each country.

European Union Network for Health Technology Assessment

There is a European initiative to encourage greater co-operation in health technology assessment that has been funded by the EU, called EUnetHTA (European Union Network for Health Technology Assessment). It is a voluntary collaboration between agencies conducting health technology assessment, that has developed a standard model for conducting joint EU-level HTA (37). European Union funding for EUnetHTA will end in 2020, with a small chance of extension until mid-2021.

Proposal for New EU Legislation

New draft legislation on health technology assessment was presented in 2018. It proposes that clinical assessments of health technologies – including medical devices – will be conducted jointly between member states, and that application of the resulting joint clinical assessment reports, summarizing the therapeutic added value of technologies, will be mandatory by all countries. The proposal does not cover reimbursement decisions, which would remain the independent and exclusive remit of each individual member state. The proposed legislation has faced serious opposition particularly from large EU member states, so it is uncertain if it will be adopted.

References

- Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, signed at Lisbon, 13 December 2007. Article 168, Public Health.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2017.117.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2017:117:TOC.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2017.117.01.0176.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2017:117:TOC.

- Council Resolution of 7 May 1985 on a new approach to technical harmonization and standards (85/C 136/01). OJ C 136, 4.6.1985, p. 1–9. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31985Y0604%2801%29.

- European Commission. Commission Notice — The ‘Blue Guide’ on the implementation of EU products rules 2016. Official Journal of the European Union, C 272, 26/07/2016 59:6-7. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2016:272:FULL&from=EN.

- Council Directive of 20 June 1990 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices (90/385/EEC). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:01990L0385-20071011&from=EN.

- Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14 June 1993 concerning medical devices. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1993L0042:20071011:en:PDF.

- Directive 2007/47/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 September 2007 amending Council Directive 90/385/EEC on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to active implantable medical devices, Council Directive 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices and Directive 98/8/EC concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market; Annex II, paragraph 10(c). Brussels: Council of the European Communities, 2007. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/sectors/medical-devices/files/revision_docs/2007-47-en_en.pdf.

- Directive 98/79/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 1998 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:01998L0079-20120111&from=EN.

- Fraser AG, Daubert JC, Van de Werf F, et al. Clinical evaluation of cardiovascular devices: principles, problems, and proposals for European regulatory reform. Report of a policy conference of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1673-86.

- Kramer DB, Xu S, Kesselheim AS. Regulation of medical devices in the United States and European Union. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:848-55.

- Kramer DB, Xu S, Kesselheim AS. How does medical device regulation perform in the United States and the European union? A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2012;9(7):e1001276.

- European Commission, DG SANTE. Report 2017-6255. Joint Assessments of Notified Bodies designated under the Medical Devices Directives. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/audits-analysis/overview_reports/details.cfm?rep_id=105.

- European Commission. Medical Devices Guidance document 2.4/1 Rev. 9 June 2010. Classification of medical devices. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/10337/attachments/1/translations.

- European Commission. Manual on borderline and classification in the community regulatory framework for medical devices. Version 1.18 (12-2017). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/12867/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

- European Commission. Guidelines on the qualification and classification of stand alone software used in healthcare within the regulatory framework of medical devices. MEDDEV 2.1/6, July 2016. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/17921.

- European Commission. Clinical evaluation: a guide for manufacturers and notified bodies under directives 93/42/EEC and 90/385/EEC. MEDDEV 2.7/1 revision 4. June 2016. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/17522/attachments/1/translations/.

- Commission Decision of 7 May 2002 on common technical specifications for in vitro-diagnostic medical devices, OJ L 131, 16.5.2002, p. 17–30. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1562145866445&uri=CELEX:32002D0364.

- European Commission. Clinical evaluation of coronary stents. Evaluation of clinical data – A guide for manufacturers and notified bodies, MEDDEV 2.7.1, Appendix 1. December 2008. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/10324/attachments/2/translations/en/renditions/pdf.

- Byrne RA, Serruys PW, Baumbach A, et al. Report of a European Society of Cardiology-European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions task force on the evaluation of coronary stents in Europe: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2608-20.

- Byrne RA, Stefanini GG, Capodanno D, et al. Report of an ESC-EAPCI Task Force on the evaluation and use of bioresorbable scaffolds for percutaneous coronary intervention: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1591-601.

- Official Journal of the European Union, 2017/C 389/02; 2017/C 389/03; and 2017/C 389/04. Publication of titles and references of harmonised standards under Union harmonisation legislation. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AC%3A2017%3A389%3ATOC.

- ISO 14155:2011. Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects – Good clinical practice. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/45557.html.

- ISO 13485:2016. Medical devices – Quality management systems – Requirements for regulatory purposes. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/59752.html.

- ISO 5840-1:2015. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 1: General requirements. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/61732.html.

- ISO 5840-2:2015. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 2: Surgically implanted heart valve substitutes. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/51314.html.

- ISO 5840-3:2013. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 3: Heart valve substitutes implanted by transcatheter techniques. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/51313.html.

- ISO 5910:2018. Cardiovascular implants and extracorporeal systems – Cardiac valve repair devices. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/66356.html.

- EN ISO 5840-1:2015. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 1: General requirements (ISO 5840-1:2015). Available at: https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/f?p=204:110:0::::FSP_PROJECT,FSP_ORG_ID:39118,6266&cs=14F6CB28102D5BE3DD091B95E7697C61E.

- EN ISO 5840-2:2015. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 2: Surgically implanted heart valve substitutes (ISO 5840-2:2015). Available at: https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/f?p=204:110:0::::FSP_PROJECT,FSP_ORG_ID:39905,6266&cs=1D1013EE301DE06E9F7B23773F96ED9B9.

- EN ISO 5840-3:2013. Cardiovascular implants – Cardiac valve prostheses – Part 3: Heart valve substitutes implanted by transcatheter techniques (ISO 5840-3:2013). Available at: https://standards.cen.eu/dyn/www/f?p=204:110:0::::FSP_PROJECT,FSP_ORG_ID:30948,6266&cs=1611CD01AE96FF9E511E7011D53711E80.

- Wu Y, Butchart EG, Borer JS, Yoganathan A, Grunkemeier GL. Clinical evaluation of new heart valve prostheses: update of objective performance criteria. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1865-74.

- Butchart EG, Borer JS, Wang M, Grunkemeier GL. Sample size requirements for clinical trials of transcatheter valve replacement and valve repair devices. Structural Heart. 2018;2:485-9.

- Kramer DB, Tan YT, Sato C, Kesselheim AS. Postmarket surveillance of medical devices: a comparison of strategies in the US, EU, Japan, and China. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001519.

- Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2001 regarding public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32001R1049.

- Fraser AG, Butchart EG, Szymański P, et al. The need for transparency of clinical evidence for medical devices in Europe. Lancet. 2018;392:521-30.

- European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA). HTA Core Model. Available at: https://www.eunethta.eu/hta-core-model/.